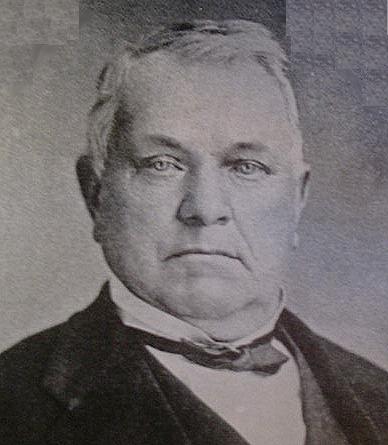

John Purdue

John Purdue, founder of the La Fayette Agricultural Works and of Purdue University, etc., was born in Pennsylvania in 1802, and when very

young was taken by the family in their removal to Adelphi, Ross County, Ohio. From 1826 to 1830 he taught a select school in Piqua County, Ohio,

during which time he was enjoying the "happiest hours of his life." He first visited La Fayette in 1837, and permanently located here in 1839,

forming a partship with Moses Fowler in the mercantile business in the Hanna building on the north side of the square, under the firm name of

Purdue & Fowler. In 1840 the business was removed to the Taylor corner, now occupied by the La Fayette National Bank. Afterward Mr. Fowler

retired from the business and Mr. Purdue continued until 1848, when the firm of Purdue, Stacey & Co. was organized, adding a wholesale department.

This relation continued until 1861, when the firm of Purdue, Brown & Co. was formed, who were subsequently bought out by Dodge, Curtis & Earl. In

1855 Mr. Purdue engaged in the commission business in the city of New York, under the firm name of Purdue & Ward. In 1865 he returned to La Fayette,

where he remained until his death.

-- Biographical Record and Portarait Album of Tippecanoe County, Indiana (1888) Page 681

. . . In all that tended to help develop this county Mr. Purdue was ever foremost. He was a broad minded, consevative gentleman, who left his impress

on the community in which he lived for so many years.

It has been well said that among the very few means of perpetuating one's name, that of founding or endowing some public institution is perhaps the most

enduring monument that can possibly be reared to one's memory. Harvard, Cornell, DePauw and Purdue educational institutions will in all human probablility

outlast the solid granite shafts and bronze tablets placed here and there to mark the spot where rests the mortal remains of some illustrious dead.

--

Past and Present of Tippecanoe County Indiana (1909) Page 305

In the eastern slope of the Alleghenies, in Huntington County, Pennsylvania, a short distance from the "blue" Juaniata River, a few loose stones and decaying

logs in the midst of a small clearing mark the humble spot where, on October 31st, 1802, was born the founder of Purdue University. Hemmed in on all sides by

a dense forest, and being difficult of access, it is but seldom that one happens upon this isolated place, but to the one who chances upon this small clearing

no sign of life is visible, save, possibly, the whir of a flock of surprised partridges, or the warning sound of a "rattler," as he slinks beneath the stones that

once constituted the fire place of the cabin, for such was evidently the nature of the building. Standing upon the place, one can easily imagine its appearance;

a low house, constructed of rudely hewn logs, the cracks being filled with clay, containing two, or possibly three rooms, and as many doors and windows. At one end,

on the outside, a huge stone chimney, likewise plastered with clay, surmounting the capacious fire place opening within, completes the picture.

From the clearing, a narrow roadway winding in and out among the trees and boulders leads down the side of the mountain to the main road, leading to the ancient village

of Shirleysburg, once a thriving place in the earlier history of our country.

It was over this road that John Purdue traveled to and from the low stone church, situated scarcely a mile from the clearing, and that stands today, except for the modern roof,

as it did a hundred years ago, and in which divine service is still held at regular intervals. It was here that there were instilled into Purdue's youthful mind those principles

that made him so successful in after life; the fruits of which success we now enjoy. Here, as well as at the village, he heard those tales of the busy outside world that led him,

later, to leave home in search of greater things.

John Purdue was the only boy in a large family, his father being a poor hard working, honest pioneer. At an early age he showed a taste for intellectual culture, and was enabled

to attend the common schools. He made rapid progress in his elementary studies and after a few years of great industry, improving every opportunity, he became quite

proficient in the English branches of study and was himself called to the schoolroom as a teacher.

While still young, his father and family emigrated to Ross County, Ohio, and thence to Worthington, a small town near Columbus.

After several years as a most successful teacher Mr. Purdue visited Marion County, Ohio, where he purchased a quarter section of land and at once went to farming. We shall not

follow him step by step in his commercial life. It was a magnificent success for the individual, but not less so for education in Indiana.

He first came to Lafayette in 1837, although he did not locate permanetly until the year 1839, when he opened a store of general merchandise in connection with a Mr. Fowler, in a

building on the northeast corner of the public square. Soon after, he struck out on his own account and accumulated a vast fortune, which was ever freely distributed for benevolent

and educational purposes. His commercial operations in New York City, during the civil war were characterized by wonderful business foresight and unflinching integrity, so much so

that Mr. Purdue's name became a tower of credit in that city. It has been said of him, "He was truly the king of produce merchants in that great metropolis during his business residence

there."

In 1869 he announced himself as an independent candidate for Congress and came very nearly being elected, his competitor being the Hon. G.S. Orth.

To those conversant with the history of education in Indiana it is a well known fact that "Purdue University had its origin in an act of Congress, dated July 2, 1862;" also, that "On May

6th, 1869, the Legislature voted to accept a donation of one hundred and fifty thousand dollars from John Purdue." This latter statement, however, gives no adequate idea of the great heart

and unselfish purpose that actuated that magnificent gift. That offering, and subsequent ones, represented the life earnings of a busy and earnest man; not money made by extortion or by

questionable speculations.

John Purdue, by application and toil, amassed a fortune and then gave it up in the hope that the young men of the future might enjoy the advantages that unkind fortune had denied him.

During the summer of 1876, Mr. Purdue had not enjoyed good health, but nothing serious was apprehended. On the afternoon of September 12th of that year, however, he visited the university and

returned to the Lahr House, where he had apartments. Later in the evening, having retired to his rooms, he was found dead; the cause of his death being, doubtless, apoplexy, with which he had

been threatened. A commanding spot on the university campus, in front of the main building was chosen as the site of the grave, which is now marked by a simple hedge.

The funeral was largely attended, and Emerson E. White, then president of the university, delivered a funeral oration at the grave. John Purdue's life was one of honesty and uprightness. He

seized every opportunity of doing good that presented itself, and it is through his last and crowning act that the students of this university enjoy the many privileges now spread before them.

Although his birthplace is unhonered and almost unknown, Purdue University stands as a monument to him who made possible the building up of a university, than which there is none better.

"No gleaming shaft nor granite rock,

No sculptured pile of cold, insensate stone,

No chiseled epitaph of empty praise

Marks his last resting place.

Himself without a home, he reared a place

Where Science might abide and Learning dwell,

Where Art should flourish long, and hold her court

And grant to every worshipper his meed.

He sleeps--and towering here above his couch,

The products of his genius and his toil

Speak lounder far than wrought and figured stone,

Of life well lived and labor nobly done.

--1900 Purdue University "Debris" Pages 19-22

At the time of the conflict in the state-legislature about the location of the school that was to result from the Land Grant Act of the government, John Purdue made his donation with the

specification that the college be located in Tippecanoe County. As a memoir to his gift the institution was officially chartered as Purdue University.

John Purdue, the only son in a family of eight children, was born in Shepardsburg, Pennsylvania, on October 31, 1802. His education was gathered in bit by bit as he moved from his birthplace

to various settlements in Ohio. Starting at the age of twenty he taught school for four years at Piqua, Ohio. Shortly afterward he became interested in the commission business and with that in

view he visited LaFayette in 1837. Two years later he took up his permanent residence here and started what developed into one of the most thriving commission houses in this section of the country.

Parallel with his business activities were his civic interest; at various times he was a member of the City Council and the School Board. At the outbreak of the Civil War he organized and

equipped the "Purdue Rifles," an unofficial group of public spirited citizens. During the war they saw actual service as a border patrol.

He encountered a more or less distasteful experience as a politician and newspaper owner when he took oposition to a reconstruction policy and became a candidate for representative. In order to augment his

campaign he purchased the LaFayette Journal. The venture proved a failure, for he was defeated in the election.

When the matter of the University was undertaken he devoted his entire interest to it and for a number of years was the most influential member of the Board of Trustees. On the first day of school,

September 12, 1876, he suffered a fatal stroke of apoplexy and, in accordance with his wish, he was buried on campus. His body still lies at the foot of the flagpole.

--1924 Purdue University "Debris" Pages 123-124

Purdue University in its' infancy

Purdue University in 1889

Not unlike the neighboring country is Purdue. The same mean height above the sea level is noticeable, and can not escape observation even by a stranger. This is

one of the features that render the landscapes so attractive to the numerous visitors. The land is high, which is in harmony with the minds of those living there;

also, dry, another characteristic possessed by many of the natives.

Journeying westward from Lafayette the traveler crosses the Wabash river. This beautiful stream is one of great renown. Its waters are clear and translucent. The

traveler may pause here for a short time, watching the sparkling waters slowly flow over the 40th parallel, and dancing ever onward, it at last dances lightly over

the horizon into the distance. After a wearisome ascent of the low stretch of table-land that lies in the west land, the traveler is greeted by a fresh gust of wind.

This he will immediately recognize as coming from Purdue, chiefly by its freshness, and, to a certain extent, by its windiness. If provided with a cane and a good

serviceable guide-book, the rest of his journey may be traversed with perfect ease. If any difficulty is encountered in finding Purdue, the observance of the following

direction will obviate it: After leaving the confines of Chauncey, and traveling westward, the traveler will notice a group of buildings on the right hand side of the road.

If this group does not contain among them a fine, large and elegantly equipped gymnasium, it is Purdue. If it does, however, it is not Purdue. Around the University an

air of refinement prevails, which is very gratifying. Over the University there constantly hangs a delightful and fragrant, as well as useful, atmosphere of nitrogen and

oxygen, also very gratifying. To the extreme south is the gravel road. Some thirty yards south of this is the United States Experiment Station, where they experiment with mother Nature.

To the far north, looking out over an expanse of ploughed landscape, broken here and there by smiling forest land and laughing brooklets, stands the fencing hall, guard

house, officers' headquarters, and the soldier factory. Surrounding these buildings are beautiful trees, rising into regions of perpetual air.

Between the officers' headquarters and the experiment station are the college buildings, grouped artistically around a two-sided rectangle, constructed for that purpose.

Comprising the college buildings are University hall, Art hall, Engine house, Mechanical hall, Dormitory for young men, Physical and Chemical laboratory, Pierce Conservatory,

two spaces shortly to be occupied by the projected chapel and Electrical hall, besides many beautiful minor features, too beautiful to mention. In front of University hall--the

largest and most imposing of the group--there nestles down in the smooth bosom of the extensive lawn, almost buried in dewy grass, the college tennis courts. Here is where the

members of the various tennis clubs spring lightly into the air and deftly hammer the tennis balls out into the hazy purple of distance. Hard by is the last resting place of

John Purdue, our benefactor, whose body, since his death in 1876, has serenely reposed within the shades of the many buildings created by his munificence. What could be more

appropriate and fitting?

--1889 Purdue University "Debris" Chapter 1

Purdy--The older form of this name, Purdue, gives a clue to its derivation, Pour Dieu. It has been fairly numerous in north-east Ulster since the seventeenth century. -- THE SURNAMES OF IRELAND by Edward MacLysaght

"Pour Dieu" is French, meaning "For God"

PURDUE NOTES

________

I noticed Purdue spelled P-e-rdue on the new street cars, Gentlemen, we don't spell it that way. There is no excuse for such a mistake. Change it, street car manager. It's an awful give away. -- The LaFayette Weekly Journal, Tuesday March 6, 1888

At the time he made the offer that brought the land grant college to its definite location, John Purdue was sixty-seven years of age. For thirty years he had been a leader in the business and financial life of LaFayette. Establishing his permanent residence there in 1839, he opened a store,

and continued a wholesale and retail drygoods and grocery business, with changing partnerships, for a quarter of a century. By 1845, he was enabled to erect a series of stores, known as the Purdue Block, which still are standing on the west side of Second Street between South and Columbia. This

was said at that time to have been the largest business block outside of New York City. It brought prestige to LaFayette as a center for the jobbing trade.

In the fifties, with a partner, Mr. Purdue opened a commission house in New York City for the sale of western products. The business grew, and the Civil War by increasing the demand for western pork, enriched the partners. Much of Mr. Purdue's

wealth was made in war time.

These financial benefits were the natural reward of opportunity combined with business aptitudes. Purdue's whole life had been a preparation for them. Born October 31, 1802, near Shepardsburg, Huntington County, Pennsylvania, on the eastern slope of the

Alleghenies, John Purdue was the only son in a family of eight children. The circumstances of his early life developed the steadiness, persistence and independence so marked in later years. He obtained what schooling was available near his home, and later in Ohio,

whither the family had migrated, settling first in Adelphi, Ross County, and later at Worthington, near Columbus. But it soon became necessary for the only boy to earn his own living and to assist the other members of the family.

For four years in his early twenties, John Purdue taught school in Pickaway County, Ohio. Before he was thirty, he had bought a quarter section in Marion County, Ohio, and already had obtained an introduction to the commission business out of which his fortune grew. His first adventure in this business bore testimony to his ability and character. For on very short

acquaintance his farmer neighbors entrusted four hundred hogs for him to market. He took them to New York, sold them profitably, satisfied the owners, and cleared a margin for himself. The transaction was a revelation of the possibilities in a commission business.

Purdue's first visit to LaFayette occurred in 1837. The city stood at the head of navigation on the Wabash River. It offered further opportunities, moreover, as for several years the terminus of and long an important stopping point on the Wabash Canal, then an important commercial artery, but now, like most of its contemporary canals, fallen out of use and almost of remembrance.

LaFayette was an enterprising town. Purdue resolved to trust his fortune to its growth. In 1839 he returned to what henceforth was home.

Having cast his lot with LaFayette, Purdue at once became a leading citizen. He took an active part in the life of the community. Few enterprises there were of private gain or civic betterment but solicited and received Purdue's support. His purse was always open. At various times he was a member of the city council and of the school board. He was a patron of education long

before he became a benefactor of the University. He was a stockholder and trustee of the Tippecanoe Battle Ground Institute. He presented to the Stockwell Institute the sum of $500 for the purchase of philosophical apparatus. Also he held stock in the Alamo Academy, Montgomery County. In 1872 he agreed to give to Buchtel College, of Akron, Ohio, now the Akron University, the sum of

$1,000, payable at his decease, for the founding of a scholarship. The agreement was duly executed by Purdue's administrators, and the sholarship is still available to Akron students. No less creditable than his more spectacular gifts was the cheerfulness, moreover, with which Purdue, a bachelor and one of the heaviest tax-payers in his county, always met assessment on the school tax.

Never by word or act did he countenance endeavors to overthrow the system of tax-supported schools which came into being in his days of active business. His interest in education was pocket deep.

Other activities indicative of public spirit were the organizing and equipping of the "Purdue Rifles", one of the first organizations in Indiana to respond for duty in the Civil War. The day the men entrained for New Albany for border patrol duty was not to be forgotten. Purdue subscribed also in 1865 to one-third of the stock in "The Purdue Institute", a project for a lecture hall, reading

room and library for the benefit of the young people of the city.

His other goodnesses were personal. Beneath a somewhat gruff exterior, he had a warm heart. He was kindly disposed to his associates in business, and especially to young men, whom he frequently helped toward a start in life. He was generous to those in need. Nor did he forget his kindred in Ohio. These human traits improved with age. He grew more mellow, although in another phase of character

the self-confidence and independence of his youth came later to be regarded as egotism and obstinacy. He could seriously assert "I never made a mistake in business" as a plain statement of fact.

With the versatility of a man of action, Purdue aspired to be an editor and politician. During the campaign of 1866, finding himself opposed to the reconstruction policy of the Hon. Godlove S. Orth, Representative of the Eighth Indiana District, he sought a nomination on an independent ticket, and to further his campaign purchased "The LaFayette Journal". His views on reconstruction were humane,

and did him credit. But he was not a natural politician and the adventure hurt him. It cost him friends and popularity, and reacted later to the disadvantage of the University he came to sponsor. Moreover the purchase of the paper and other campaign costs were a heavy charge upon his fortune. Though he probably did not know it at the time, he could ill afford the loss.

It was some such man as these brief notes have sketched who made his name immortal by one good deed that lives. That good deed was certainly his own. For although it is doubtless true that friends of John Purdue encouraged his munificence, he himself made inquiries into the character of foundations in other colleges and did his own investigating. He is known to have visited at least one educational

institution in the east founded by a man of wealth, and to have studied its organization and methods before making his decision, which certainly was not a sudden one. It coincided with his natural sagacity that he examine a problem from many angles. And he undoubtedly consulted with his friends on matters of detail. As an unmarried man without a wife to counsel him, the voice of friends had all the

greater weight. But the man who founds a fortune is, in last analysis, the man of independent judgment. The major decision was unquestionably his own. Purdue was his own giver.

When Mr. Purdue made his gift to the University, he builded better than he knew. It alone remains to keep his memory green. Without this monument he would long ago have passed into oblivion, as have so many men of equal or greater wealth and reputation in their day. Mere wealth was already passing from his hands. Mr. Purdue illustrates a common experience that it is easier to found than to conserve a fortune,

though the extent to which his estate was involved did not become apparent till his death.

He had invested heavily in the LaFayette Agricultural Works, organized to manufacture harvesters and other farm machinery. Incompetence and extravagance of his associates wrecked this business. Also he incurred heavy responsibility in the building of a railroad line form LaFayette to Muncie. As a result, though his obligations to the University were fully met as were all other claims on the estate, there was

little left for the heirs except a mass of uncollectable accounts and notes.

Amid these business misfortunes, Purdue should have found a solace in the rising institution which bore his name. To some extent he did so. On its material side, he was most helpful to the University. He was given a free hand in the selection of the site, and the planning and erecting of the first buildings. These tasks were quite within his powers. On the educational side, his opinion had less value,

though of this he could not be persuaded. Selection of the faculty and determination of a course of study lay outside his experience. But he was prone to interfere. Friction grew so serious that for several months he absented himself from all meeting of the board. He was out of sympathy with President Shortridge, but in the early months of President White's first year he gave evidence of renewing interest.

He had again undertaken to assist the building program of the University and to contribute toward its general expenses when on September 12, 1876, he was stricken with apoplexy. In deference to his wish he was buried on the campus of the University.

In the present age some dispute exists as to the relative advantages of State institutions and privately endowed. Some champions of academic freedom argue for the latter as really the more liberal, being free from any bogey of the politicians. Whatever be the merits of this controversy, there can be no doubt that Purdue University is favored in her double parentage. The State has been most generous. And

in John Purdue, the modern young American, who is an individualist at heart, has a benefactor worthy of respect. A pioneer in early associations, and throughout his life a successful individualist, John Purdue is a sturdy, yes a noble, representative of his times.

--PURDUE UNIVERSITY, Fifty Years of Progress by William Murray Hepburn & Louis Martin Sears, 1925 (Chapter VI, "John Purdue")

The nineteenth century dawned on a freshly foaled America thrashing awkwardly to gain its sovereign feet, to take its first difficult but brave steps toward nationhood. The times were fluid

and uncertain, yet they produced men and women of certainty--individuals who knew what had to be done, then did it.

One of them was John Purdue, the only son among the nine children of Charles and Mary Short Purdue (who are believed to have been married about 1790 in Maryland). He was born in the Purdues' sturdy log cabin, eighteen by twenty feet, on the eastern lower slope of Black Log Mountain

on October 31, 1802, in an area called Germany Valley not far from Shirleysburg, Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania.

Few men are so blessed by the accident of birth as to be reared alongside a unique experiment--the beginnings of a new nation dedicated, in spirit if not always in fact, to the sanctity of individual freedom. John Purdue was one so blessed, born less than two decades after the signing of the Treaty

of Paris which established the new country as a nation; his arrival was only fourteen years after the new United States Constitution became the law of a land previously governed by the law of royal caprice, or not governed at all.

Eli Whitney had filed his first patent for the cotton gin only nine years prior to John Purdue's birth. The Whitney invention had so profound a social effect on the new nation that many of the problems resulting from its creation and use still exist.

A mere two years before Purdue's birth in the Pennsylvania mountains, John and Abigail Adams first occupied the newly built presidential manse in Washington, D.C. At about the same time, the United States Congress arrived to move into the unfinished capitol in the same city--then not yet a city,

much less a federal capital.

John Purdue was not a year old when young America paid France $15 million in cash for the Louisiana Territory, a purchase of a vast stretch of interior North America that doubled the young country's area, giving it its heartland and breadbasket, though straining its pocketbook.

Purdue turned nine years old a week before William Henry Harrison and 920 militia regulars and Hoosier volunteer troops from the government's Vincennes outpost, some on horseback, some afoot, arrived at a spot a short distance downstream from the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash rivers.

There on a small flat-topped rise along Burnett's Creek (once called Dead Gulch Creek) they fought an obscure but smart little skirmish with a swarm of peevish braves led by a Shawnee mystic, a thirty-six-year-old, one-eyed rogue named the Prophet, also known as Laulawasikaw, (some authors spell it "Laulewasika"), literally, "loud mouth."

The area was a forlorn, often-flooded wilderness of malarial swamps, mosquitoes, copperheads, rattlesnakes, a variety of varmints in great number and varying degrees of ferocity, a hellish tangle of vines and undergrowth, and other capricious vegetation pervasive on the lonely, dark edge of the Great Prairie. Yet, men seemed willing enough to kill or maim one another over it.

In the predawn hours of November 7, 1811, they did so--200 casualties in all. It became known as the Battle of Tippecanoe, the precursor some theorize of the War of 1812, although that may be quite likely an undeserved historical approbation. Not incidentally, the battle was won by the higher moral persuasion of the white man's rifle balls which, Laulawasikaw had been able to

convince his naive young braves, would turn magically to sand at the muzzles and fall harmlessly. That they did not raised some serious doubts and caused no little consternation (not to mention bloodshed) among the Prophet's braves about the credibility of his leadership. Eventually, he was driven in disgrace and dishonor from among his own, who included, ironically, his highly

respected brother, the great Chief Tecumseh.

As a nine-year-old schoolboy, John Purdue at best could have been only slightly aware of the momentous events taking place on the wilderness frontier several hundred miles west of his central Pennsylvania world. How could he really care about such things happening along the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers when the fishing was so good along Aughwich Creek that meandered through one of

the many valleys between the Allegheny ridges? How could he imagine--especially one who at age twelve "hired out"--that one day he would make a mercantile fortune, immortalize his name, and live out his years only a relatively few steps from that historic battleground.

Growing up in those times, Purdue and his contemporaries took on as personal qualities many of the same traits that eventually gave dimension to the character of the new, evolving nation. He was steady, independent, and persistent to the point of being downright mule-headed at times. But he was also endowed with a penchant for hard work, undoubtedly acquired from a boyhood dominated

by it, and, as the Purdue mythology would surely have it, and unimpeachable integrity. He was the equivalent of his surroundings.

Along the way, John Purdue also acquired a trader's acumen. With that and whatever other qualities and combination of resources he mustered, he became one of that fraternity of select nineteenth-century farmer-trader-merchants who came to learn the fine and rare art of winnowing profit from the vaguest hint of commercial opportunity, to learn to stay just far enough behind the leading

edge of America's westward-moving frontier to make their fortunes from it.

* * *

Most of the details of John Purdue's early life in Pennsylvania were either not recorded or are lost. We know vertually nothing about his father, Charles, and mother, Mary, or why they came to choose a mountain wilderness as home for their nine children. We can surmise that the father could earn the family living there. John was halfway down the family skein. He had four older sisters,

Catherine, Nancy, Sarah, and Eliza. Margaret, Susan, Mary (Polly), and Hannah were younger. Another sister, name today unknown, died in infancy.

One's birth and rearing in a log cabin does not necessarily imply a childhood of poverty and dire need. In John Purdue's case, the evidence appears to be strong that, although the family had to work hard, it was well fed and comfortably housed, and had a modest savings. Father Charles worked at several jobs but was primarily a charcoalburner at a nearby iron smelter. That may account for

the fact that the frugal Purdue family had enough money to make the difficult and expensive trip west to Adelphi and later to Worthington, Ohio, in 1823 when John was twenty or twenty-one.

* * *

The surname Purdue is considered to be English, existing in England long before the era of the French Huguenots from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth centuries. Nevertheless, the name is subject to several theories as to its derivation. Perhaps it was French in origin and that it was originally Perdue, but only Purdue in its rarer forms. Even on the early Pennsylvania frontier,

John's family name often was spelled Perdue; early census takers even spelled it that way. Regardless, one theory has it that the name had its origin in the latin Per Deum, through the French, par Dieu--the battle cry of the Norman knight, or possibly the motto emblazoned on his pennon, surplice, and shield, or often a name given to those who used it as an oath. Another theory suggest that

the name derives from the French perdu, meaning "lost," a word used to describe a foundling, or a soldier on outpost duty cut off from his troops by an enemy.

John Purdue's lineage may go back to William Purdue of Closworth, Somersetshire, England, head of a fairly widely known family of bellfounders who were also established in Ireland. In fact, William himself was buried in Limerick Cathedral and a favorite epitaph chiseled on his tombstone in this couplet:

Here lies a bellfounder honest and true,

Till the Resurrection, named Purdue.

Though most sources indicate that the Purdue family was English (albeit established in Ireland as well), Charles Purdue is believed to have come to America from Scotland. Other sources indicate he may have been born either in Maryland or Virginia about 1765 and migrated as a young man to central Pennsylvania. The correct family name is not altogether clear; Charles is identified in the 1800 census of

Shirley Township in Huntingdon County as "Charles Purdin" and in the 1810 census as "C. Purdoo." Even as a young man in Ohio, John may have occasionally signed his last name as "Perdue" or Perdoo." The evidence that suggest it, however, may simply be a case of an incorrect deciphering of his handwriting.

An early and pervasive belief that the Purdue origins were in Germany, possibly because of some vague, assumed connection with the Pennsylvania home in Germany Valley, has long been discounted. The only safe conclusion one may draw from the available information about the Purdue ancestry is that today it seems rife with confusion.

* * *

At the age of eight, John Purdue was sent to the Pennsylvania community's one-room school, down a rough and rocky road near the foot of Black Log Mountain not far from the Purdue cabin. What formal education Purdue had, he obtained there. He was good in school, especially in "the English branches of study," and for several years in Ohio, he eked out an existence as a schoolteacher in the

same kind of classroom where he had been taught.

The westward trek of the Purdue family to Ohio took most of the summer of 1823, an arduous and tragic journey. Nancy, one of John's older sisters, died en route; his father died not long after the family arrived in Ross County, Ohio, at the town of Adelphi. The route of that trip is not known today. The family probably crossed over the ridge and traveled south fifty miles through the Aughwich Creek valley,

a much traveled trail used by both Indians and pioneers between the Susquechanna and the Ohio country that brought them to the National Road. A principal east-west artery between Cumberland, Maryland and (at that time) Wheeling, Virginia, the road bore outbound settlers westward and the products of early pioneer farms eastward.

At Wheeling, the Purdues very likely boarded a flatboat to Portsmouth, Ohio, thence traveled overland north up the Scioto River valley to Adelphi, a tiny community tucked away in the northeast corner of Ross County in south central Ohio. It is a region with quaint place names such as Tar Hollow, Rattlesnake Knob, Yellow Bud, and Kinnickkinnick. Not long after John's father died, Mary Short Purdue and her

daughters packed off for Worthington, Ohio, a settlement about twenty miles north of Columbus. Worthington was a "road's end" community at the edge of a frontier from whence the courageous, intrepid, and/or foolhardy left civilization at its fringe and plunged headlong into a primeval wilderness.

As the American frontier crept westward, the greatest supply of eligible bachelors seemed to move with it; thus, Worthington was a likely spot where Mary Purdue could help her daughters find husbands--a necessity in those days, especially in a family with seven marriageables. In due course, the Purdue family at Worthington enlarged by six sons-in-law. Eliza never married.

John, then about twenty-one, struck out on his own. The exact sequence of events that comprised his Ohio years is hazy. We do know that he taught in Pickaway County in a select (i.e., private) school. He was successful at it but also nearly poverty-stricken since he was paid the handsome stipend of $10 per month--a sum so "handsome," in fact, that he was "warned out" of one township for fear he would become an indigent charge.

Yet, in retrospect, Purdue recalled his periods as a schoolteacher as "the happiest days of my life." One of his pupils from those days was Moses Fowler, a farm lad born near Circleville, Ohio, who was Purdue's junior by thirteen years. They later became business partners in Adelphi and Lafayette.

Fowler later married Eliza Hawkins of Hamilton, Ohio. Purdue, the lone son among the nine Purdue children, never married, and it was often observed, even in later years, that although he was always a gentleman he was also always extremely shy in the company of women.

A preponderance of evidence indicates that John Purdue probably taught in Ohio schools from about 1826 to 1830. One account says that he was recommended by the president of Athens University (now Ohio University at Athens) for a schoolteaching job in 1831 at Little Prairie, south of Decatur, VanBuren County, Michigan, and taught there for a part of that year.

Purdue had put together enough capital by 1831 to purchase 160 acres in Marion County, Ohio, for $900. He paid $450 down, with the balance to be paid when convenient and without interest. He farmed the land for about a year and sold it for $1,200 in 1832. That sale with its $300 profit to himself was an early and classic example of the entrepreneurship that typified Purdue's business style. During the year

he farmed, his reputation for shrewd but honest dealing brought his neighbors to him with a request that he market their hogs for them. It was a new experience for Purdue, but he took 400 animals to market, probably at Cincinnati, paying the farmers a fair price, and collecting a $300 commission for himself.

From that exhilarating adventure, Purdue, astride his horse, developed a profitable farm products brokerage, covering as much as a fifty-mile radius in and around Adelphi, Worthington, and Columbus. As word spread, Purdue's reputation for fair dealing spread also; he became popular among the residents of the area who, until then, had no convenient market for their foodstuffs. Purdue created one; in fact, he became

their market. Ohio was being domesticated; the state had embarked upon an ambitious public works program to build a network of canals and to extend the National Road from Wheeling, across Ohio to Richmond, Indiana. Work camps east of Columbus needed food; farmers needed markets. Purdue satisfied both needs. On that basic economic axis turns the world of capitalism.

* * *

In 1833, in partnership with Fowler, Purdue opened a general mercantile business in Adelphi. He was then thrity-one; Fowler was eighteen and a journeyman tanner. Although they were young and relatively inexperienced in mercantile trade, their business prospered. So what motivated them to take the risks inherent in moving it to an obscure, depressing little river settlement with an uncertain future in west central Indiana?

Conventional wisdom states that John Purdue first saw Lafayette in 1837, two years before he and Fowler moved their business to that community. Rather convincing evidence suggest that Purdue was aware of the western Indiana possibilities as early as 1834. He first passed through the city either by stagecoach or on horseback as early as the late fall of 1836 on a business trip to Galena, a northwestern Illinois community near the

Mississippi River, where Purdue and Fowler seemed to have conducted an extraordinary amount of business by mail.

The 1834 evidence includes a land transaction in Adelphi in which Jesse Spencer conveyed to John Purdue 240 acres in Tippecanoe County on December 9 of that year. Spencer bought it through the federal land office in Crawfordsville for $850. The parcel lies in Fairfield Township at the northeast corner of Creasy and McCarty lanes east of Lafayette. One assumption is that the Spencer conveyance was in trade for goods

purchased at the Purdue-Fowler store in Adelphi and that the agreed-upon price was that paid at the original government purchase. Quite likely, Purdue first inspected the land on his western trip in 1836. Purdue retained ownership for twenty-three years, adding parcels, buildings, and other improvements, then sold the farm in 1857 to William McCarty for $10,000.

Did John Purdue move to Lafayette in 1839 (again, as is generally believed)? or perhaps earlier? While still in Ohio, he was in a dispute with an Illinois man over a tax matter involved in the purchase and sale of an unspecified parcel of land near Prophetstown, Illinois, northeast of Moline on the Rock River. In a letter to his antagonist dated August 5, 1837, Purdue wrote that "I have closed my business in Ohio and am nearly ready

to leave the state for good," adding that he should write to him next at Lafayette, Indiana, "where I expect to be located permanently again next spring and where I expect to spend some time this fall."

Whether 1837, 1838, or 1839, the date is important only as a date; when Purdue and Fowler arrived to reestablish their Adelphi business, Caleb Scudder, first white child born in Lafayette, was a ten-year-old tad. Purdue was thirty-six or thirty-seven, Fowler twenty-three or twenty-four. What they found was a settlement of mostly saloons, a brawling river village where pigs freely rooted in dirt streets or cooled themselves in the frequent

mud wallows, where, undoubtedly, a tanyard, a foundry, cabinet shop, and other appropriate rivertown industries throve along the Wabash. There were several churches; Purdue arrived for good the same year, 1839, as the town's first church bell, founded for the tower of Saint John's Episcopal Church.

A visitor from Massachusetts in the 1830s described Lafayette as "like all the rest of the Western villages we have seen, filled with stumps, hogs, horses, cattle, and Indians." Lafayette survived the vituperation, having been blessed, apparently, with people blithely indifferent to the opinions of outlanders. The populace had been toughened by the earlier scorn and derision of its older neighbor, Crawfordsville, where wags referred to

the town as "Lay-flat," "Laugh-at," or similar distortions of language.

Over land, Lafayette was not easily accessible except by bone-jarring wagon or buggy ride through rutted mud paths or over plank roads--or by horseback. Lafayette's almost total economic orientation was to the river, without which Lafayette had no raison d'Ítre.

The town was founded by William Digby, the son of a veteran of the War of 1812, a tall and handsome ne'er-do-well cardplayer. At age twenty-two, he poled up and down the upper Wabash either by keel boat or dugout, carrying items for his itinerant trading business with the Indians. His familarity and knowledge of this stretch of the Wabash led him to attend a government sale at the federal land office in Crawfordsville on Christmas Eve 1824.

Digby knew that commercial vessels could navigate as far upstream as the present site of the city and probably no further--even when the current was high in the spring.

No doubt Digby was also aware of the site of an abandoned Indian trading post built along the Wabash at Lafayette by James Wyman. Wyman thought the site was an ideal location, especially from the standpoint of the river's seasonal levels. He erected a post building and one or two others for his residence but abandoned it to the undergrowth and overgrowth after most of the Indians withdrew from the region in 1819 and 1820. Wyman remained

in this area but never claimed ownership, and it thus became a part of the land eventually offered for sale at the United States land office at Crawfordsville years later.

In 1821, Tippecanoe County was believed devoid of white men except for Peter Longlois, the French trader who, with his Indian wife and two children, occupied a trading post at the mouth of Wildcat Creek northeast of what is now Lafayette. But only three years later, Digby and others bid frantically for purchase of Wabash valley lands as white settlers began to move westward and northward.

At the 1824 land sale, Digby dug deep and bid bravely against a man named Major Whitlock for 84.23 acres on the east side of the river and finally acquired them for $231.63. He hoped to establish a trading post, albeit in an area tangled with hazel and plum brush vines and trees of every description. In the spring of 1825, he and a bartender friend, Robert Johnson, who was also a surveyor, surveyed the rough site--a difficult chore

because of the nearly impenetrable underbrush--and divided 50 acres of it into 140 lots. On May 25, 1825, inspired by the triumphant return to this land of the Revolutionary hero General Marquis de LaFayette (who had made a stop at Jeffersonville on the Ohio River), Digby named his little plat "LaFayette" in the Frenchman's honor. Two days later, he filed the plat at the Crawfordsville land office. It covered the area bounded by the

river and the present Lafayette streets of Sixth, South, and North.

Not known for his reliablity or astuteness, the improvident Digby sold most of his plat to Samuel Sargent for $240--$1.71 per lot--or a gross profit to Digby of $8.37. Within a month, he sold the balance for a paltry $60 dollars.

Digby first operated a general store, then bought a ferryboat which he operated across the Wabash River for many years, ferrying pioneer farmers and their goods to the Lafayette markets. Eventually, Lafayette became the head of Wabash navigation and an important commercial hub. But over the years, Digby engaged mostly in drinking, card-playing, and the brawling that usually resulted therefrom. As Digby's prestige as the founder of the town

diminished, his notoriety as a public nuisance grew. He died at age sixty-two in 1864, "in reduced circumstances" his death notice called it, apparently unaware that had he retained just one-tenth of his original purchase, he would have been a wealthy man. As it turned out, he was a virtually penniless railroad bridge watchman in Attica when he died.

William Digby never knew that "his" Lafayette, Indiana, is perhaps the only town ever founded by the town drunk.

* * *

There was this itinerant who wandered through Tippecanoe County on his way to nowhere in 1827. Lafayette was only two years old at the time. You can read about him and the problem they were having with itinerants in those days in the minutes of the seventh meeting of the Lafayette Board of Justices. This itinerant was different. His name was John Chapman and they called him "Johnny Appleseed." Downstream on the Wabash, near West Point,

Johnny accidentally killed a rattlesnake while clearing space for a seedling apple nursery, and they say he suffered acute remorse for the rest of his life because he had carelessly killed a living thing.

* * *

What impressions John Purdue may have absorbed on his first visit we do not know. Descriptions of the time spoke of a dreary, unkempt settlement of log cabins and frame buildings. What was it about this surly little settlement on the Wabash floodplain that held such attraction? John Purdue was a trader, an entrepreneur, a capitalist. He would give something for anything and take something for anything. The successful traders of the world

are those with a clear focus on the future. Purdue was far more interested in what Lafayette could be than how it might have appeared at the moment. For example, he could not have overlooked the coming of the Wabash and Erie Canal to Lafayette, a part of a vast system of "improvements" that in a spate of financial lunacy Indiana had decided to undertake. As a businessman, he had to be aware that the advent of the canal had raised the price

of wheat from forty-five cents to one dollar a bushel while dropping the price of salt from nine dollars a barrel to four.

Such were the intimations for a growing and healthy commerce in Indiana, although intimations created at the expense of the state's solvency. It was the kind of prosperity which tended to camouflage the bankrupt condition of the public treasury: a state debt of $10 million which carried a $479,000 annual interest charge, far more than the revenues from the mismanaged canal system could satisfy.

Yet, the plain fact was that a rich land was coming to commercial maturity; river towns such as Lafayette, though nondescript, dreary little huddles, were on the make; the fact of public insolvency seemed to matter little or was dismissed outright as a temporary political trauma. Life near the frontier's edge pulsated. Make the area more easily accessible and the opportunities to exploit its richness seemed endless.

Considering the high cost of its construction, the canal itself prospered relatively briefly, sputtering along for little more than three decades but destined for an ignominious death in the 1870s. Notwithstanding, the area's long-range possibilities seemed undeniably clear to Purdue and, collectively, were undoubtedly the principal factors that influenced his decision to tie his wagon to the Lafayette star, despite a thriving business and a solid, statewide reputation in Ohio.

Purdue and Moses Fowler displayed superb timing. They arrived in Lafayette four years before the canal, moving their dry goods and grocery business from Ohio. They made the then squalid Wabash River town in western Indiana their lifelong home, contributing mightily along the way to its eventual civility and domestication. Their firm's first advertisement appeared in an early Lafayette newspaper, the Free Press, and hawked "200 bbls. of sweet cider--just

received and for sale cheap." Purdue and Fowler, before they ended their partnership in 1844, were known to sell any merchandisable goods.

Lafayette--the star city on the Wabash--may have had (as the late Paul Fatout so colorfully observed in his 1972 book, Indiana Canals) "a bucolic air of caliker and butternut jeans." But in business dealings, its citizens were far more astute than the small-town jaspers they may have appeared to be. The atmosphere virtually reeked with an all-consuming need to make a dollar. Growers, shippers, and merchandisers, Purdue and Fowler included, pursued the Wabash Valley's riches,

benefiting from the then booming canal and river shipping business which could move products northeastward via Toledo and the Great Lakes to the east coast or southward via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. By 1851, in the shipping season, as many as thirty-one steamboats bound to or from Evansville, twenty-five from or to Cincinnati, and twenty to or from Pittsburgh tied up at the Lafayette docks; others were out of Louisville, St. Louis, and New Orleans. Later, the Wabash and Erie Canal

was extended south to Evansville, increasing the volume of stuffs shipped from, to, or through Lafayette via canal packet or steamboat. The last commercial riverboat at Lafayette steamed away in 1861.

But at one period during the short-lived canal's heyday, Lafayette annually exported more than foty thousand barrels of flour and pork, well above one million bushels of corn, and more than four million pounds of bacon and lard, in addition to huge quantities of wheat, oats, butter, soap, cheese, potash, hides, and tanbark. The town had a drydock for canal packet boats. It had commission houses (Purdue's was considered one of the largest and finest west of New York City), livery stables, and even a boatmen's infirmary.

Fowler quit his partnership with Purdue in 1844 to pursue other business interest in commerce, banking, the railroads, and Benton County farmland northwest of Lafayette. Eventually he came to be known as Indiana's richest man. In the ensuing years, Purdue continued his business interest with other partners--usually men much younger than himself--men on the way up whom Purdue chose to give a helping hand. As early as 1844, Purdue purchased the downtown Lafayette real estate needed for the Purdue Block. In 1847,

the block was completed and in 1848, he founded the company known as Purdue, Stacey and Company, which included wholesaling as well as retailing. He also had partnerships with Samuel Curtis and Oliver H.P. McCormick and had formed, with L. (for Lazarus) Maxwell Brown, Purdue, Brown and Company which occupied a major portion of the Purdue Block bounded by First and Second, and Columbia and South streets.

Whether John Purdue made the correct decision in moving to Lafayette was never in question. As he said in reference to his business career, "I never made a mistake in my life."

* * *

The land around about was full of copperheads and rattlers and you watched where you stepped, but the wabash River and the creeks that fed it were full of fish--bass, trout, pike, and sauger. What roads existed were mostly mud in winter and dust in summer, but you could haul a wagonload of corn into Lafayette for three cents or less from the Wea country where yields went anywhere from forty to ninety bushels an acre. That was in 1848.

In 1849, you did not go into Lafayette too often. The roads were a fright and there was a cholera epidemic--two or three deaths for every four or five cases; what doctors there were worked nearly to exhaustion. They used up the town's supply of dry flannel and red pepper mustard and salt they rubbed on those who came down sick. More than half the population had gone in all directions out to the country, intending to return only when the cholera abated, if it did. Country folk were shy about going into town.

The new railroad was going in at about eight rods a day, and by 1852, Lafayette had five rail and three plank roads to it, good houses, fine churches, and blocks of neat, brick store buildings. And the Wabash and Erie Canal throve. So did the saloons. So did the Democrats with Franklin Pierce and William Rufus King, who got elected the country's president and vice president, and who left no vestige of Whigging in all of Indiana.

* * *

The 1849 cholera epidemic was one of the darkest moments in the young town's brief history. It lasted about six weeks. Thousands fled the city in panic, many of them camping along Wea Creek south of the city. In one brief period at the outset, only a handful of untrained nurses, their helpers, and one local doctor, Elizhur H. Deming, a member of the faculty of the Indiana Medical College at LaPorte, were available to treat the sick.

They worked day and night, seemingly in vain; eight hundred died, about fifteen of every one hundred citizens. Those who stayed in town reported later the eerie sensation of living in a city of deadly silence--broken only by the occasional sound of wagon wheels creaking over the town's gravel streets as they carried coffins to Greenbush Cemetery. Three Lafayette prostitutes had fled to a rural cabin where they fell ill with the disease. Those who discovered them there immediately torched the cabin, immolating the sick women inside.

Business and commerce slowed and nearly stopped. Many merchants closed their shops and businesses as they fled; many never reopened. John Purdue survived the catastrophe, seemingly none the worse off financially or physically.

If there was a darker moment than the summer of 1849, it may have been the summer of 1854 when the second cholera epidemic broke out, most likely becuase of a failure to correct the conditions that were the source of the first. Six hundred citizens, mostly adults, died in the 1854 miasma. Several movements to clean up the heaps of garbage in alleyways and along city streets had been started as a result of the 1849 epidemic, but nothing seemed to get done.

Such efforts broke down in political squabbles, despite the fact that Lafayette had prided itself on being an early (1833) Indiana city to establish a board of health, a development that grew out of citizen complaints that too many people were urinating in the Wabash River.

John Purdue must have been deeply moved and concerned by the 1849 event, but his particular interest, besides making money, was in education, engendered partly from his own school-teaching years in Ohio, partly from a lifelong regret he often alluded to that he had not had more opportunity for formal education himself.

When Indiana rewrote its constitution in 1851, provision was made for free schools. Quickly the following year, the Indiana General Assembly adopted legislation empowering common councils in Hoosier communities to appoint boards of education empowered, in turn, to levy school taxes. The Lafayette Common Council in 1852 appointed the city's first school board. John Purdue, Israel Spencer, William P. Heath, Jacob Casad, and Samuel Hoover were its first appointees. Purdue was a member of that first board's first committee to seek school

building sites--the fist being the Southern School at Fountain and Third streets. It was later replaced at the same site by the Tippecanoe School which was razed in recent years to make way for a community center.

An 1854 Indiana Supreme Court decision found the taxing portion of the new free school statute flawed and therefore unconstitutional. A year later, Indiana free schools found themselves without operating funds. Across Indiana the public schools closed--all but in Lafayette where, thanks to the personal largess of John Purdue, they remained open. Indiana public schools opened again in February 1856, but not until 1860 was the law finally corrected to the satisfaction of the Indiana Supreme Court.

Purdue served a term on the Lafayette Common Council in addition to his appointment to the school board. But he preferred to commit most of his community stewardship and resources to other matters. His life as a leading citizen, businessman, and budding philanthropist was interrupted in 1855 when he formed a new company in New York with John S. Ward, then twenty-five, an employee of an eastern pork packer named J.B. Thompson. Their New York commission house, known as Purdue and Ward, did a spectacular Civil War business

as a chief supplier of pork and pork products to the Union armies. Purdue became a rich man. Presumably, so did Ward. Purdue also became a tower of financial stability and integrity in New York and was known among his colleagues in trade as the "King of Produce" and/or "Mr. Pork." Still, he retained his residency in Lafayette and his interest in his Lafayette businesses and the community at large.

Purdue made his first trip to New York as a Lafayette businessman in 1847. (He may have made a trip to the eastern seaboard while an Adelphi businessman.) The purpose of his 1847 trip was to despose of $100,000 in pork products he and his partner Brown had shipped to New York and to purchase goods for wholesale and retail business in Lafayette. He left Lafayette in August and returned in October. New York visits became more frequent for Purdue. But he was getting older; trips to the East from Lafayette were long and arduous. He began to spend

more time in New York and less in Lafayette; in 1855, after establishing Purdue and Ward, he lived there most of the time for a decade.

Purdue returned to Lafayette in 1865, his fortune in war profits intact. He was then sixty-three, and in most of his remaining eleven years until his death in 1876, he did those things which stamped his name forever on the age. They were years that gave him the public attention he secretly loved and whetted his deep interest in educational matters but left his fortune in a shambles, an executor's nightmare.

Purdue's widely known munificence and his comparatively large fortune brought him a plethora of suggestions from the well-meaning as well as from the misguided as to how and to whom he should dispose of his wealth. He was as busy in his later years making sure it was disposed of properly as he had been in earlier times acquiring it. It was a tough job; he waded through a great number of suggestions, investigated each of them himself, and made up his own mind. He tried to make his money work to the advantage of the entire community. Obviously,

his primary interest was in doing the things that would improve education. That interest was described in George W. Munro's writings as "pocket deep" and went back many years before the gift that brought him immortality as the university's chief benefactor.

Generous though he was, Purdue had a vanity as wide as the Wabash River and, as a member of the first faculty, Harvey Washington Wiley, put it in his own memoirs, a vanity "as innocent as that of a child. He was certain that any opinion he had was the only correct one on any subject."

Wiley recalled that although Purdue was not a member of any church in Lafayette, he often gave generous sums for religious and philanthropic causes and had given $1,000 toward the construction of the Second Presbyterian Church. When it was completed, he was invited to the dedicatory service. He entered the sanctuary just as the members of the congregation rose to sing the first hymn. Purdue thought it was a gesture in his honor and said in a voice heard throughout the sanctuary, "Keep your seats, ladies and gentlemen; don't mind me."

When Purdue played Santa Claus, the gifts he loved to give the most were those with his own name on them. Thus, when a "Purdue Institute" in downtown Lafayette was suggested shortly after his return to Lafayette, he agreed to bankroll one-third of its cost, $25,000. The institute was to be an all-inclusive facility combining public library, reading rooms, lecture hall, and art gallery. One of the letters to him urging his contribution to a facility that was to bear his name may have been too pretentious, and he probably lost his enthusiasm.

Signed by a gentleman named "I. Rice," the letter read in part, "It would be a child of whom any man living might feel honored in being called its father, while his heart should throb with the leap of quicker pulsations, as he saw unfolding the future, ever-growing promise of its ripe manhood."

As 1866 dawned, Purdue felt obliged to enter politics, probably the biggest mistake he ever made, in spite of his own self-encomium that he had never made one.

His calling to the political wars was based primarily on his view that federal policy with respect to post-Civil War Reconstruction should be less harsh and more compassionate. He became an independent candidate for Congress and faced a strong and popular Republican incumbent, a famed Lafayette attorney and poet named Godlove S. Orth, who sought a third term as a representative from Indiana's eighth district. To further his campaign, Purdue bought the Lafayette Journal from James P. Luse for $30,000 and became its editor--a decision which

compounded his original error. The Chicago Tribune, referring to Purdue as "John G. Purdue of Lafayette, Ind.," (The reference to "John G. Purdue" is the only instance this writer has ever seen of John Purdue's name used with a middle initial. Whether he had a middle name--and if he did, what it was--could not be documented.) came out strongly for the reelection of Orth, opining that since Purdue's purchase of the Journal, "its editorial columns have been almost exclusively devoted to proving that the Convention system is all wrong.

His platform is short, ambitious, and, if it means anything at all, it means bread-and-butter."

Running as an independent was literally true for Purdue; he did things his own way. Some of his methods were no more virtuous than those of his opponents, some of them worse. He knew nothing of political acuity, nor much about editing a newspaper. In one notable example of illogic, referring to his refusal to print a letter from a reader who wanted to use a false name, Purdue wrote editorially, "I don't like these underhanded licks, anyway. Whenever I write an anonymous communication I always sign my name to it."

An opposition editorial in the Lafayette Daily Courier read:

Daily we have evidences of that wonderful intellect which in colossal grandeur o'ertops the small statesmen of the day. Mr. Purdue says himself, and he surely wouldn't lie about a little matter of that kind, that as he grows older his brain expands, and he takes "enlarged views," not visible to the clouded comprehension of weaker minds. The expansion of his brain is such that in filling an order for a campaign hat the other day the hatter took the measure of the Court House Dome and it fit him exactly. Besides, he understands the great "commercial interest."

He can tell the weight of a hog by sight and recite its pedigree by the curl of its tail.

Orth defeated Purdue by 118 votes. He was beaten, the Indianapolis Daily Sentinel editorialized in Purdue's obituary a decade later, "through the base treachery of men who had been pledged to his support." It is quite likely also true that Purdue, as a politician, was his own worst enemy. He not only lost the election, but many friends and immense popularity. The adventure hurt him as well as the university of which he became the chief sponsor three years after his ill-fated congressional campaign. He was left with a residue of hard feeling, a

newspaper he no longer wanted, and a pile of campaign debts that, though he did not know it at the time, he could ill-afford.

Despite the setback, Purdue seemed undeterred by the experience and managed to retain not only his good nature but his interest in civic and educational matters. He continued his membership as a trustee of the Tippecanoe Battle Ground Institute as well as an interest in the Alamo Academy in Montgomery County and the Stockwell Institute, to which he is known to have made contributions of "scientific and philosophical apparatus." His interest in higher education extended beyond Purdue University; while working to get the doors open at the new campus a mile or so

west of the courthouse, he agreed to provide $1,000 as a deferred gift, payable upon his death, to Buchtel College, now the University of Akron, Ohio.

Another enterprise, apparently a product of Purdue's generosity, was the Purdue Rifles, a company of Lafayette-area men whom he equipped for the Civil War--a group that, legend has it, helped drive the rebel Morgan Raiders out of southern Indiana. Probably it is more accurate that the Purdue Rifles served on border patrol along the Ohio River. Later, the same military group was supposedly active in "chasing Copperheads out of northern Indiana and Illinois." (Copperheads were Northerners who sympathized with the South.)

There is also a record of a "Purdue Silver Mine" in which Purdue had an interest. At various times throughout his adult years, Purdue loaned money or paid delinquent taxes to help friends or colleagues about to lose all. Such charity left him with such absurdities as unneeded canal dockage, warehouses, a paper mill, two hotels, and uncounted parcels of real estate scattered hither and yon and of which he was (Munro wrote in later years) "not overly fond."

As a bachelor, Purdue never gave a thought to the money he spent on his own rather simple needs and wants. He lived most of his life in well-furnished rooms at the Lahr House in downtown Lafayete. He had an ample personal library of about three hundred volumes, many of them religious or biblical references. He dressed well and was considered by the eligible women of the city as a rather handsome gentleman, though he never had, so says Munro, "an affair of the heart."

Toward women and womanhood, Purdue held a strange and starchy attitude that today would mark him as rather an odd Victorian eccentric. To Purdue, women were apparently unapproachable, fragile personae of moral porcelain to be placed upon high pedestals surrounded by chastity moats. But such was the generally accepted nature of morals and mores of mid-nineteenth-century America.

A rare glimpse of Purdue's views on the subject of women and the courtship thereof is contained in the only personal letter among the aggregate of his papers in the Purdue University Special Collections; the rest are either business or legal documents.

Dated December 29, 1836, the letter Purdue wrote was to a Miss Ann Knauere as he waited in Columbus, Ohio, for a break in wintry weather to make what is presumed to have been his first journey to Lafayette. Purdue was then thirty-four. Just exactly who Miss Knauere was is a mystery, but Purdue called himself her "sincere friend," though even in his letter he was stiffly formal, addressing her in the salutation as "Madam." Very possibly she was a daughter of the merchant under whom Purdue apprenticed. The letter was, peculiarly, mostly a rather lengthy essay

on "the impropriety of young ladies keeping the company of gentlemen at night."

He wrote:

Not having much to do at present but read, write, talk, etc., concluded I would scribble a few lines for your amusement. I did expect when I left old Delphi [Adelphi] two weeks ago I should likely be at Lafayette, Indiana, ere this. A part of the time the weather was so extremely cold that I could not form a resolution to face the coldness of the west winds, therefore I am still here in Columbus and its vicinity: amusing myself sometimes in the busy crowd about the taverns at Columbus, at other times in smaller circles in the country disposing of time as cheap

as possible and with as much ease as convenient. Columbus is really very pleasant at this time but much crowded. Some of the hotels are full to running over, there are a great many visitors in from different parts of the state, the Supreme Court in session and the legislature including all makes a very crowded city. Mr. Havens was married on yesterday to a Miss Squires, a very pretty young girl. This was disposing of another bachelor in the right way: The way that I should like to see a few more go: right into the arms of a fair young lady. . . .

I have reflected considerable since I saw you on the impropriety of young ladies keeping the company of gentlemen at night after the family retired to bed and I have come to the conclusion that it is a habit that ought to be abandoned by every young lady that has any claim to respectable society.

The practice is never attended with any good results but frequently with very serious and lamentable consequences to the character of young ladies, and I believe it has the attendance in some degree to cast a shade of some consideration upon

everyone that practice it: it has certainly the effect of depreciating that pure and unspotted character of real moral worth that ladies should possess. Recollect few men are what they profess to be. Whenever a gentleman calls to

spend the evening with you and inclines to tarry after the family retires you have then cause to suspect his motives. Few men have any regards strictly speaking for the reputation of young ladies and it is in the dark houses of night when

all evil men carry their designs into effect. The night is the highway robber's time to plunder his neighbor's property. The adulteror waiteth for the night and baser than the vilian on the highway betrays the honor of his bosom friend.

Deep layed crimes hide their odious heads in day and haunt the seats of Society at night when they think all is safe that no eye sees. When night is the settled time to execute all the accursed evils in the land. Some other time, then, I

think might be chosen for young ladies to make their marriage contracts than in the darkness of night as the object of private company between young ladies and gentlemen is to form a social acquaintance: But of which matrimonial contracts are

to be formed and upon those contracts measurably depend all the future happiness or misery of our time on earth. It being a subject of more seriousness than almost any other specially so far as earthly happiness is concerned it being a subject of

such importance to everyone that is concerned in it therefore every step that has the least reference to it cannot be observed with too much caution and prudence in every particular. In regard to keeping night company in private apartments I have

frequently been astonished at mothers who permitted their daughters to receive almost any company that would call. Mothers should never in my opinion permit a daughter to keep the company of any after they retire to bed--there is one certain fact

that is the gentleman that is seeking a wife would make a choice of one who had never kept night company with any man. The reverse is also true, the gentleman that seeks the company of a young lady to enjoy her society at night is not seeking a wife.

While I am on the subject there is another fact that I will notice: Every fallen monument of female reputation I believe had its origin in keeping night company. And every one that has wept and mourned over their own sad misfortune and ruined characters will tell you the ill misspent time of keeping night company was the only cause of [their] wretchedness and misery today. I have written you or rather scribbled a long string on this one subject. If it does not meet your appreciation excuse my pen, but I think it certainly will and it would give me much pleasure if

you would adopt my opinions as given. There is another important fact that ladies and gentlemen both neglect too much that is reading. Reading good authors on such subjects as is calculated to instruct the mind and to aid in forming correct principles is highly necessary and it is the duty of every one to attend to it as much as lies in their power. There is nothing that appears so beautiful in a young lady as to have a mind well based on correct principles and have some knowledge of the different leading topics that pertain thereto. Every one has not perhaps time

to read as much as he should like to, but everyone has time to read more I think than they do. I presume you're getting tired trying to read my scribbling. I will therefore begin to wind up and close. My trunk has never arrived. As soon as it comes or very soon afterwards I will move for the west without the weather should be very bad. I think very long to get west and I presume I shall think as long to get back. If I can return against the first of March I will. My respects to any of my friends that enquire of me and you see proper to give. My health is reasonable

good. My friends are well. You must write to me direct to Lafayette, Indiana.

Receive my best wishes to your self and others

Your sincere friend,

John Purdue

Miss Ann Knauere

Columbus O. Dec. 29, 1836

* * *

Purdue was once described as a "valiant trencherman," enjoying with great relish such goodies as walnut pickles, brandied peaches, and mince pie--especially those prepared by the mother of his partner, Mack Brown, at whose home he spent a great many convivial evenings. He was especially fond of oysters; in season, he and Brown would have a barrel shipped from the East Coast for a stag dinner lasting "unto the wee hours of the morning." Though Purdue did not drink, even he, in the spirit of such affairs, was known to have taken a snort from a demijohn of rare whiskey

kept in the Brown basement. Purdue's portly figure in later years seemed to bear out his penchant for rich foods.

If he had any real extravagance, it was travel. He was known to leave his home in the Lahr House for months on end as whim or occasion dictated. Especially did he enjoy train travel and used visits to his sixteen-hundred-acre Walnut Grove farm near West Lebanon as an excuse for a train ride. Evenutally, Purdue invested in an early, narrow-gauge railroad, the Lafayette, Muncie, and Bloomington (Illinois), which later became a part of the Lake Erie and Western, which became the Nickel Plate and is today a part of the Norfolk and Western system. The line was begun by

Lafayette investors and Purdue's love of railroad travel made his financial interest in it inevitable. He even contracted to build the Lafayette-Tipton section. Purdue was also a heavy--in fact, the principal--investor in the Lafayette Agricultural Works late in his career. The firm manufactured farm implements of a variety, one writer later said, "in which the farmers seemed not at all interested." Both investments, plows and railroads, later proved to be drains not only on his fortune but his personal health.

Beyond his letter to Ann Knauere in 1836, there exists little that tells us about the Purdue psyche. His existing personal correspondence was rare, and even that deals primarily with business matters--the ordering of stock for his business establishments and so on. He devoted his entire life to tangibles, although the intangibles and the abstract were not beyond him. But he was not considered an erudite individual who could have perhaps easily defined a personal philosophy beyond simple Christian belief. He is known by his deeds much more than by his words, although

that does not mean he was inarticulate. To speculate, he was simply a quiet, self-assured man who seemed to yearn for the formal education, perhaps in the classics, he was never able to have beyond the readings in his own personal library. These must have been treasured moments of solitude for the "good old man" as he began to approach the biblical three score and ten.

If he was overly self-conscious about his lack of capital "C" culture because of his lack of early schooling, it may have been because of his inablity to throw into English conversations the well-turned Latin or French phrase that his educated friends knew. But his own reading in history, politics, philosophy, and theology served him well. It is correct to say that he was lacking in formal, institutionalized education but absolutely inaccurate to say he was uneducated.

One of Purdue's hallmarks, despite his bachelorhood and a mercantile life spent mostly in the company and presence of adults, was his love of children. Many a Lafayette boy remembered him as the donor of his first pocketknife. Early summers invariably produced a John Purdue ritual. He would ask Mrs. Jane Clark Harvey, a prominent Lafayette woman who was the daughter of Dr. O.L. Clark, a pioneering physician in Tippecanoe County, to "collect a carriage full of girls" for an all-day outing--Purdue holding the carriage reins--that always ended with a visit to the confectioners

where ice cream, cake, and candy were consumed, seemingly inexhaustibly.